America’s Most Memorable Mascots

updated

December 9, 2025

There’s something curiously nostalgic, reassuring, and even heartwarming about brand mascots. Some of the most successful characters in American marketing have smiled at us from product labels for more than a century — like Mr. Peanut, who was introduced in 1916, the Sun-Maid girl in 1915, or the Quaker Oats man in 1877. Others are newer creations, like the Travelocity “Roaming Gnome” who debuted in 2004 and quickly became a social media star.

There’s a reason for product mascots’ staying power: They work.

Mascots give brands warmth and personality. They become touchstones that we recognize, like, and trust. We may associate them with fond childhood memories, like Tony the Tiger saying “They’re gr-rr-reat!” during Saturday morning cartoons. Or they may cheerlead us through tiresome tasks; mopping and scrubbing seem less tedious with Mr. Clean by your side. Switching insurance companies isn’t nearly as daunting when a cute lizard with a British accent assures you it will only take 15 minutes.

Of course, not all mascots stand the test of time. Some evolve and endure, while others either never connect with the public at all or quickly fade into obscurity. To find out which mascots are most memorable (and why), we commissioned a survey of 1,630 U.S. residents. The results yielded fascinating insights into marketing successes and failures, the characters that matter most to different generations, and mascots that are most often mistakenly linked with rival brands.

Mascots that hit the mark

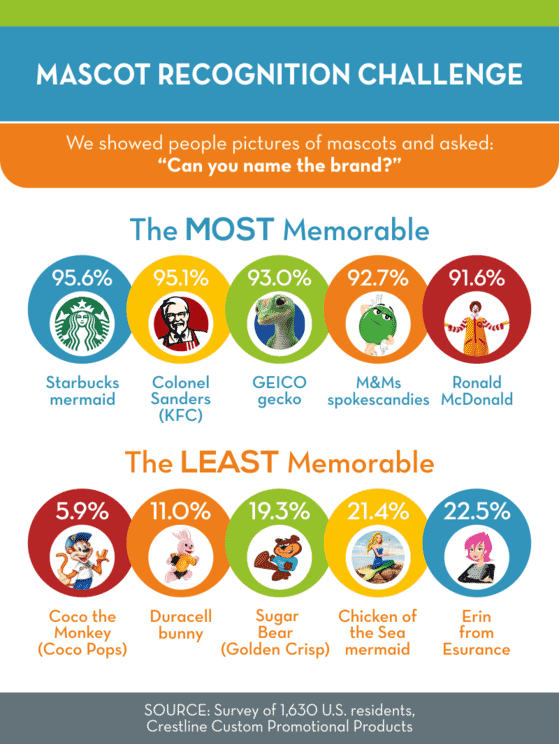

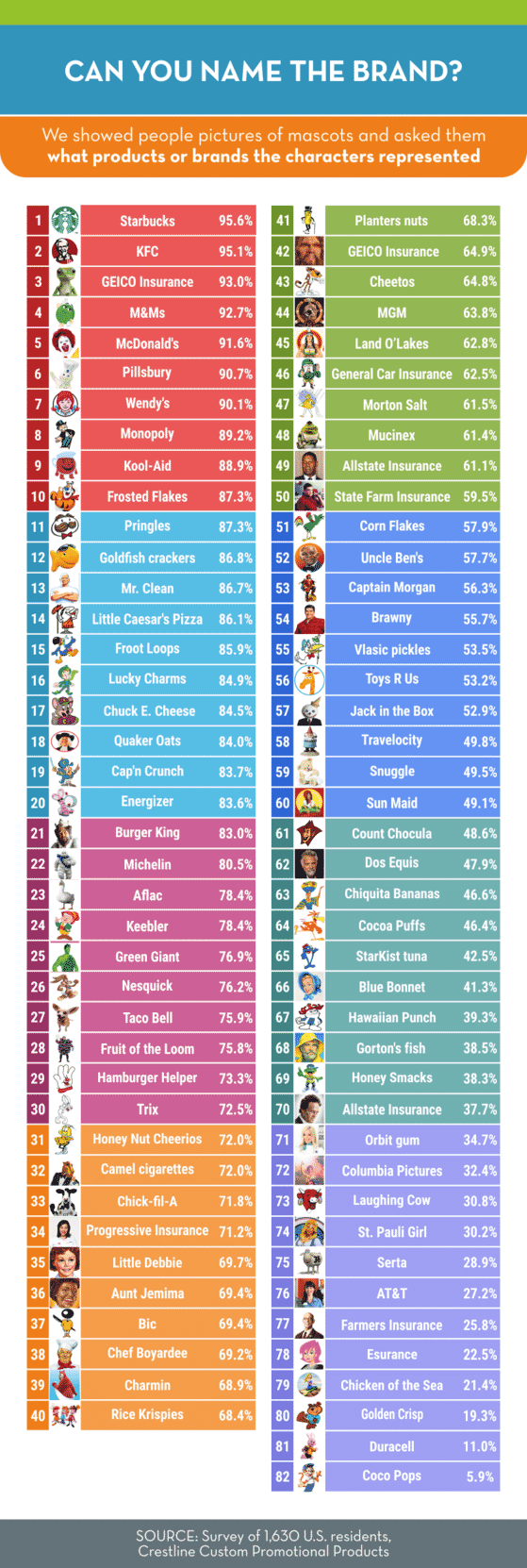

To learn which mascots are most memorable, our researchers showed people images of characters (stripped of any text) and asked them to identify the brand. There were no hints or multiple-choice options — just a blank line. With 82 mascots and 1,630 participants, it took a while to sift through all those answers, but here is what we discovered.

For those in need of a coffee mug fill-up, few sights are more welcome than the ubiquitous Starbucks siren with her flowing hair and twin tails. Of all the mascots we tested, she came out on top; 95.6% of the study participants were able to correctly identify the green mermaid with Starbucks.

In second place, Colonel Sanders was identified by 95.1% of respondents as the mascot for KFC. The logo, introduced in 1952, was based on the real-life founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken. It has gone through a few changes over the years. The colonel’s serious expression has become more jovial and his white linen suit jacket has been covered by a red cook’s apron. But the white hair, goatee, glasses, and Southern-style string bow tie have remained.

At the other end of the scale, only 5.9% of participants recognized Coco the Monkey from Coco Pops. And although the Duracell bunny first appeared in 1973 — 15 years before Energizer introduced its own nonstop rabbit as a parody — only 11% recognized the Duracell bunny compared with 83.6% recognition for Energizer’s rival version.

Here’s how the whole field fared in the challenge.

In looking at the overall results, a few patterns emerged. Food products and restaurants generally enjoy the strongest mascot recognition, trailed by insurance companies and household products. Human spokescharacters aren’t usually as recognizable as other mascots.

Although most of the characters in the top 20 have been around for generations — with an average introduction year of 1964 — a few “young” characters cracked the list. Among the oldies-but-goodies, Ronald McDonald has been repping hamburgers for 56 years. Tony the Tiger has been raving about Frosted Flakes since 1952, and Rich Uncle Pennybags first appeared on Monopoly board games in 1936. However, the GEICO gecko is thoroughly Generation Z: He was introduced in 1999 and ranked third for recognizability among study participants. In 12th place, the Goldfish cracker mascot Finn made his debut in 2005.

Are brand mascots a dying breed?

If there was a golden age of product mascots, it might have been the 1950s and 1960s. The media landscape was much simpler then, with print, radio, and television as the dominant vehicles for advertising. More brand characters were introduced during that era than in any other. However, social media has revived interest in this type of branding. Many modern mascots have large followings on Twitter and Instagram.

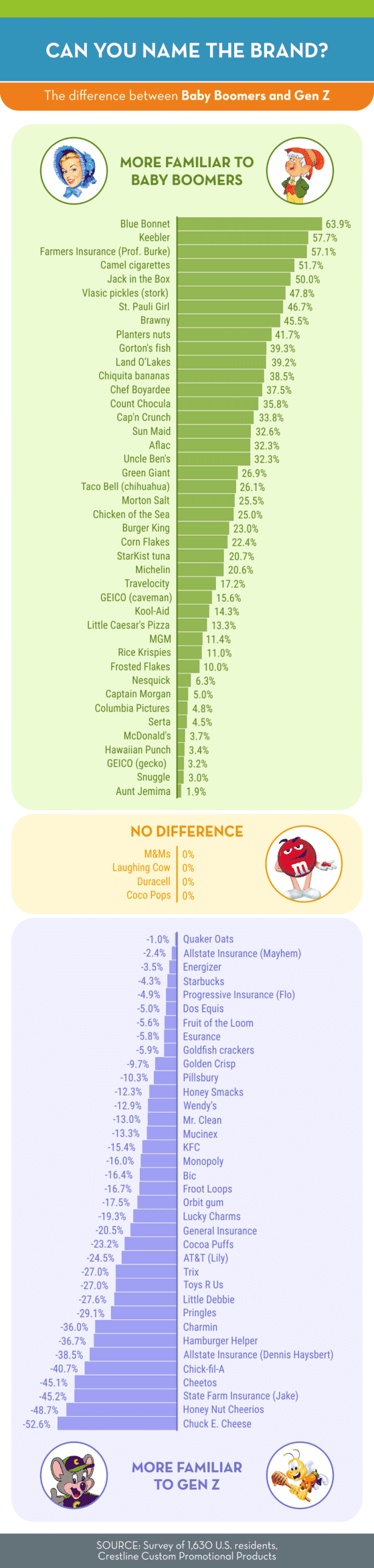

To understand the mascot life cycle better and discern which mascots might be dying out, we analyzed the results by generation. Specifically, we measured the “awareness gap” between Baby Boomers (ages 55 to 73) and Generation Z (ages 18 to 22).

Although Chuck E. Cheese has been helping children celebrate their birthdays at arcade-like pizza restaurants since 1977, the playful mouse is much less familiar to older Americans than younger ones. Chuck E. Cheese has definitely made the leap to modern media with more than 29,000 followers on Twitter and 67,900 on Instagram. Other characters that have built sizeable social media followings include Jake from State Farm, who may be more recognizable as a meme than a khakis-wearing insurance salesman, and the troublemaking character of Mayhem from Allstate.

It’s understandable that Joe Camel would be unfamiliar to younger generations born long after cigarette ads stopped. And the iconic chihuahua who said “Yo quiero Taco Bell” retired from active advertising in 2000, when most Gen Z’ers were in diapers. But other characters that aren’t aging well include the Keebler elves and the Blue Bonnet margarine girl. Some surprising entrants on the waning list include Cap’n Crunch and Count Chocula. Despite pitching youth-oriented cereals, those advertising characters haven’t connected with Gen Z consumers.

“You look really familiar…”

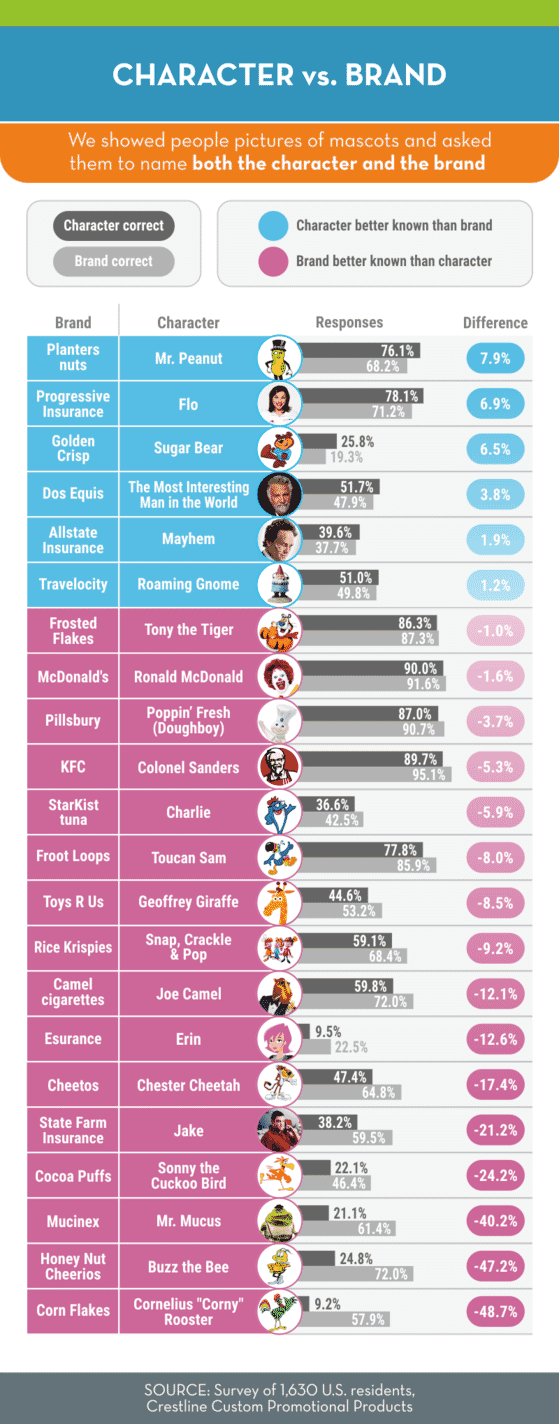

Have you ever gotten an advertising jingle stuck in your head but been completely unable to identify what brand or product it was from? The same thing can happen with mascots. When characters have names that are different from their parent company, it’s not unusual for people to be able to identify one but not the other.

One of the most compelling spokescharacters of recent years is Flo from Progressive Insurance. She’s goofy, she’s awkward, and she’s sincere. With her bouffant hairdo, red lipstick, and irrepressible spunk, Flo is on a first-name basis with 78.1% of Americans. She has 4.5 million Facebook fans and has even become a popular Halloween costume. Most people know she represents an insurance company, but they don’t necessarily know which one. Both Flo and Mr. Peanut outshine their parent companies in terms of name recognition by 7 to 8 percentage points.

At the other extreme, almost 6 in 10 study participants (57.9%) shown a picture of a green rooster knew it was from Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, but very few could come up with the name “Corny.” Buzz the Bee from Honey Nut Cheerios and Mr. Mucus from Mucinex met a similar fate. People know who they represent, but are hard-pressed to name the character.

Love ’em or hate ’em – just don’t ignore ’em

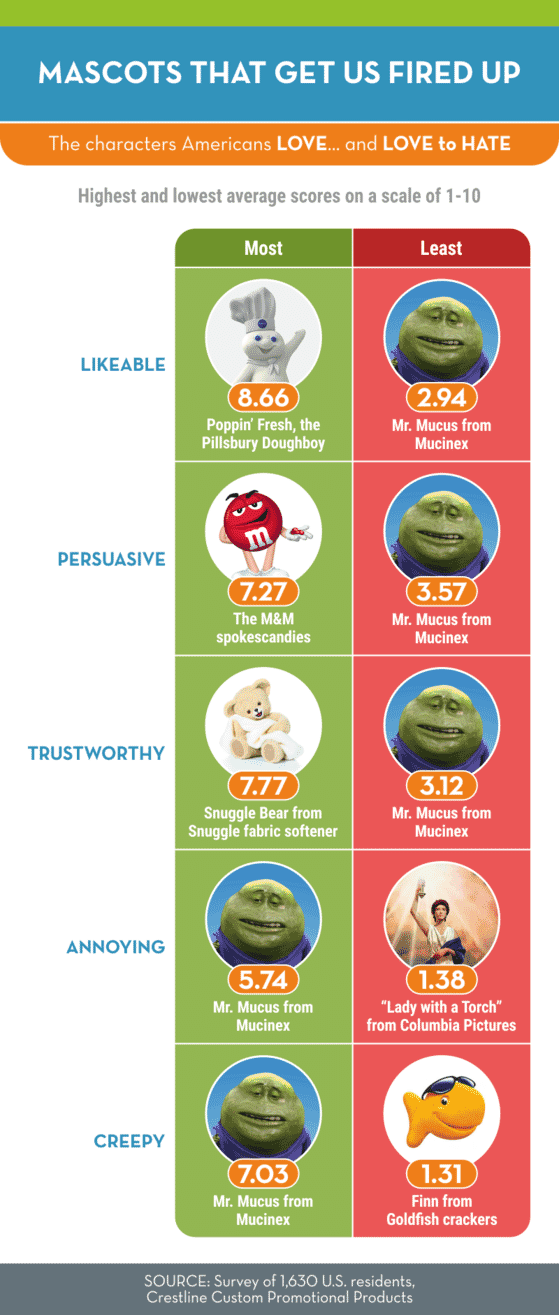

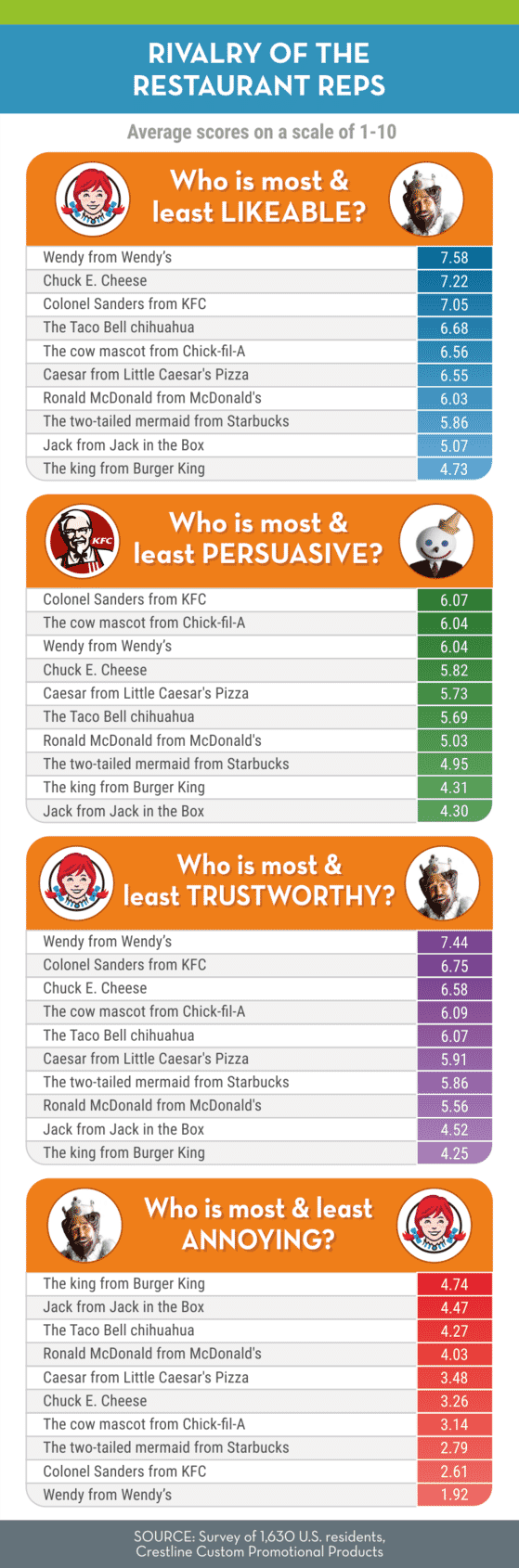

Mascots are supposed to evoke affectionate emotions, but our feelings toward them aren’t always positive. To help us understand how people feel about different characters, study participants were asked to rate brand mascots on five measures — how likeable, persuasive, trustworthy, annoying, or creepy they are — using a scale of 1 to 10.

Poor Mr. Mucus. It’s not easy being an anthropomorphized booger. The slimy green Mucinex spokescharacter dominated all of the negative categories. Mr. Mucus came in dead last out of 82 mascots for likeability, trustworthiness, and persuasiveness. And he topped the rankings for the most annoying mascot (followed by the Aflac duck) and creepiest mascot (followed by the King from Burger King and Jack from Jack in the Box).

For likeability, no other mascot can top Poppin’ Fresh, the claymation Pillsbury Doughboy who giggles adorably when poked in the stomach. Study participants rated the M&M spokescandies as the most persuasive. And Snuggle fabric softener’s cuddly bear nabbed the top spot for trustworthiness.

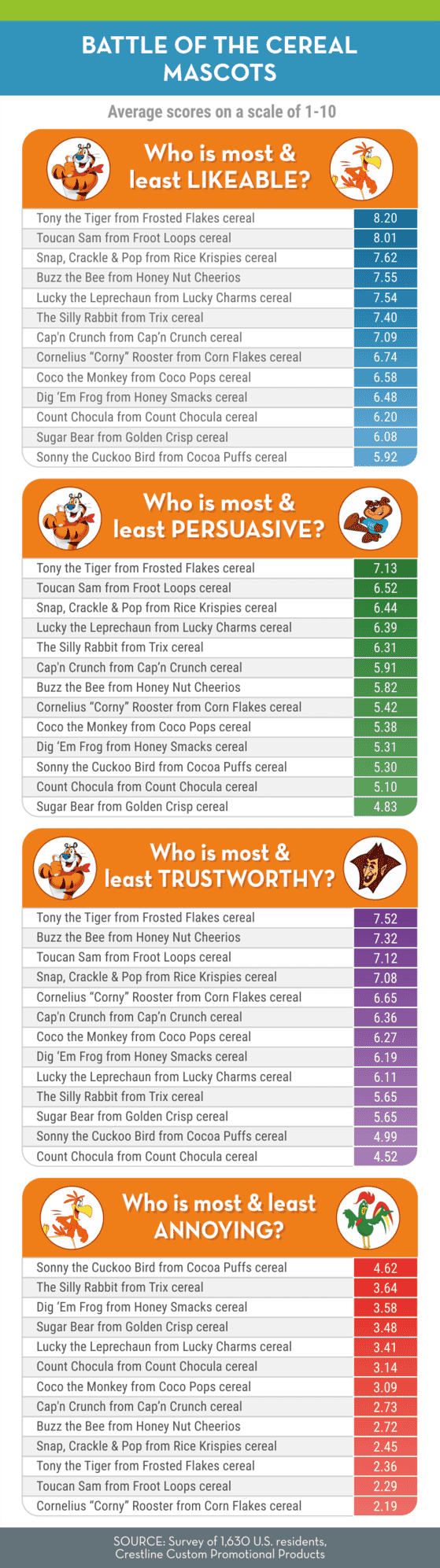

Crispy or soggy? A look at the champions of breakfast

No product category has produced a greater variety of brand mascots than breakfast cereals. Wander the cereal aisle of any supermarket and you’ll enter a magical world of tigers, bears, fairies, elves, rabbits, sea captains, leprechauns, insects, and all manner of enchanting creatures (although none are female). This highly competitive niche has yielded famous catchphrases like:

- They’re gr-rr-reat!

- Silly rabbit! Trix are for kids!

- I’m cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs!

- They’re after me Lucky Charms!

- Follow my nose, it always knows!

Still, among all these beloved characters who are completely jazzed about the most important meal of the day, there are some standouts and some underachievers. Tony the Tiger leads the pack in all of the positive categories — likeability, persuasiveness, and trustworthiness.

At the other end of the spectrum, Sonny, the cuckoo bird from Cocoa Puffs was rated least likeable and most annoying. Sugar Bear from Golden Crisp and Count Chocula from General Mills’ monster cereals (anybody remember BooBerry and FrankenBerry?) also scored poorly.

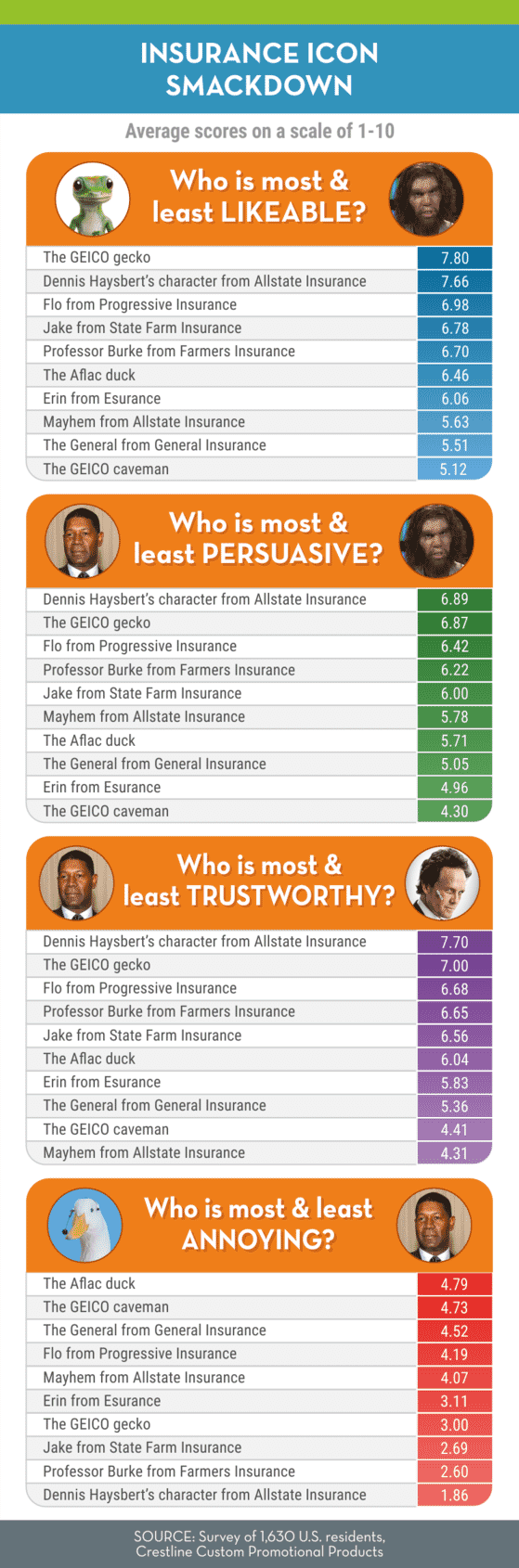

You’re in good hands with insurance mascots

The insurance industry has changed significantly over the past couple of decades, with a greater focus on user experience, connectivity, and price transparency. The digital age has also triggered an all-out insurance advertising war, with the top 11 companies spending more than $6 billion each year to get their messages out. In 2018, Allstate budgeted $887 million, topping State Farm’s $802 million effort. But both companies were eclipsed by GEICO’s eye-popping $1.2 billion advertising spend, bankrolled by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. (Buffett apparently has said if he had $2 billion to spend on advertising, he would.)

The current crop of insurance spokescharacters is fairly young, compared with other types of mascots. Allstate’s Mayhem character, played by actor Dean Winters, debuted in 2010. Flo from Progressive Insurance, played by comedienne Stephanie Courtney, appeared in 2008. The Aflac duck and GEICO gecko, both introduced in 2000, are downright long in the tooth by comparison.

Interestingly, while cereal mascots universally convey enthusiasm to connect with consumers, insurance mascots evoke a variety of emotions and embody a range of character traits. Dennis Haysbert, the deep-voiced actor who radiates gravitas, portrays an unnamed character for Allstate who led the categories for trustworthiness and persuasiveness, came in second for likeability, and also ranked as least annoying.

Other characters depict different qualities to reassure people who might need insurance. Progressive’s Flo (who’s ranked third-most likeable, trustworthy, and persuasive), seems honest, conscientious, and engaging, while State Farm’s Jake is a relatable “everyman.” Farmers’ Professor Burke, played by Oscar-winning actor J.K. Simmons, conveys experience and wisdom — he’s seen it all, and he’s got your back. Only Allstate’s comic anti-hero Mayhem evokes fear of all the unknown ways you could be in for trouble.

Some of the catchphrases popularized by these characters include:

- Are you in good hands?

- We know a thing or two because we’ve seen a thing or two.

- Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.

- 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on car insurance.

- So easy, a caveman could do it.

Human insurance mascots seem to fare better than most animated ones, as The General from General Insurance and Erin from Esurance both scored low in all the categories except most annoying, in which The General placed second, behind the Aflac duck. The main exception to this rule is the GEICO gecko, who ranked as the most likeable insurance mascot, and the second-most trustworthy and persuasive.

Create Your Winning Branding Strategy with Promotional Products.

The friendly faces of fast food

America’s restaurant and fast-food mascots are an unlikely — and even baffling — group. According to one study, 42% of Americans are afraid of clowns. Harboring heebie-jeebies for characters in greasepaint is so common there’s even a clinical term for it: coulrophobia. Yet McDonald’s and Jack in the Box remain loyal to their respective clown brand mascots that were introduced in the 1950s. In the early 2000s, Burger King resurrected a plastic-faced king character that is similarly disconcerting and was rated most annoying by study participants.

Among animal mascots, it’s probably best not to think too hard about why a rodent is the ambassador for kids’ pizza chain Chuck E. Cheese. The character started as a rat in 1977 and was redesigned as a mouse in 1995. The rat costume worn by real-life mascots at the restaurants used to have a tail, but it was phased out due to kids constantly yanking and pulling it. Chuck E. Cheese has gotten younger and hipper over the years, and he was rated the second-most likeable character by study participants. But the fact remains: He’s still a rodent.

Local health departments also might take issue with a small dog running around a taco restaurant, but that didn’t stop the Taco Bell chihuahua from nabbing 4th place for likeability and 5th for trustworthiness.

For likeability, persuasiveness, and trustworthiness, Americans lean toward the human-inspired characters of Wendy and Colonel Sanders. The counterintuitive cow mascot from chicken chain Chick-fil-A also performed well in the study. The diminutive toga-wearing mascot for Little Caesar’s Pizza fell in the middle of all of the rankings.

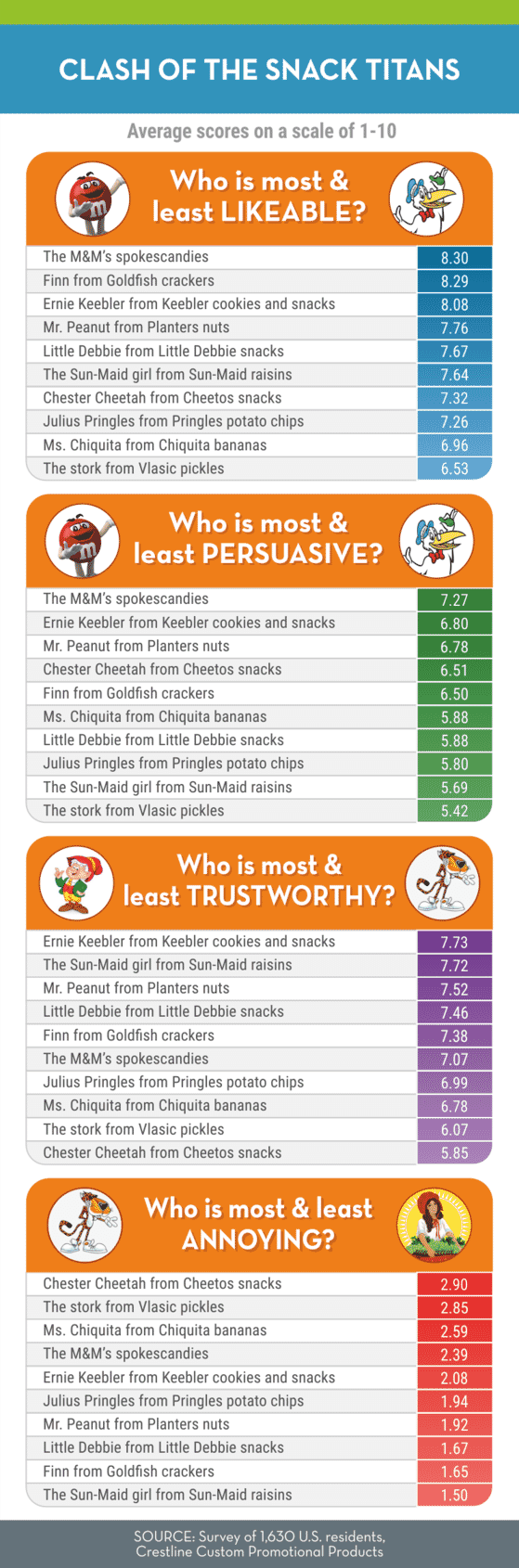

Salty or sweet? How snack mascots stack up

Snack brand mascots keep it light and sweet — even the salty ones. In this animated cohort, the women are fresh-faced maids, the men are venerable old chaps, and the rest are … well, animals. Some are also food.

As a group, snack mascots tend to be cute, sweet, and innocuous – and their scores confirm it. On a scale of 1-10, the snack mascot that study participants found “most annoying” (Chester Cheetah) only scored a 2.9. In any other product group, he’d have been near the bottom of the ranking. Overall, snack mascots just aren’t very annoying.

Similarly, compared to their brethren in other niches, snack mascots are very likeable. The M&M spokescandies were not only “most likeable” and “most persuasive” compared with other snack mascots; they also were at or near the top in the entire field of 82 characters studied.

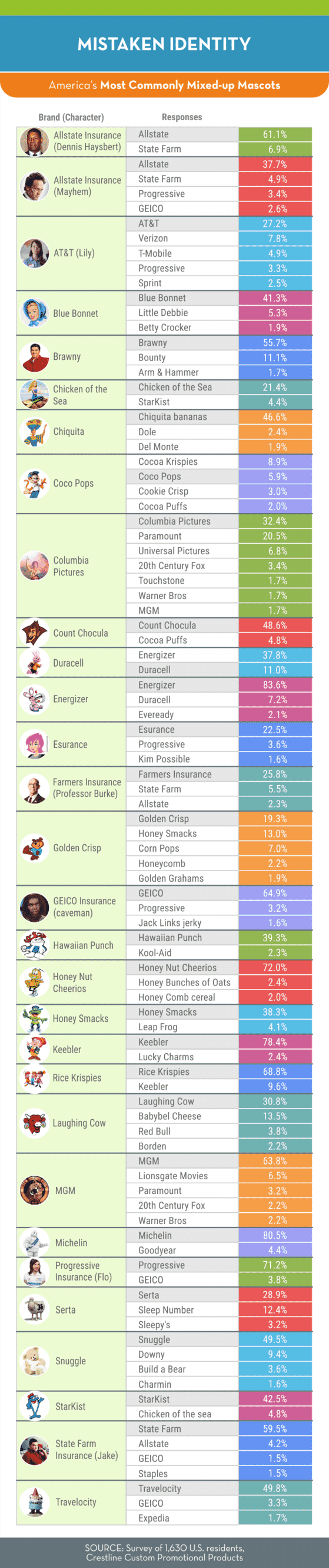

Character confusion

“Saturated” is an understatement when it comes to the marketing and media landscape. It takes millions of dollars to catch the public eye, and even then, it can be hard to differentiate products and brands. Understandably, when our study participants tried to identify brands based solely on images of their mascots, many of them got it wrong — usually close, but no cigar. Looking at those incorrect answers, we noticed many cases of “mistaken identity.” Here are the characters most often matched with rival companies.

Of all the products that get muddled in our minds, car insurance, movie studios, and canned tuna seem to be the most common. Problems seem to arise when company names are less-than-unique (like Allstate, State Farm, and Farmers Insurance) or when a niche is saturated with many similar products (like honey-flavored cereals). Strong color associations can also confound consumers. The Laughing Cow mascot’s dominant red color was mistaken by many study participants for Babybel cheese or Red Bull energy drinks, which also feature red.

Two mascots on our list were more often linked with another product than their own: Coco the Monkey from Coco Pops and the Duracell bunny. Coco the Monkey was introduced in 1963 as the mascot for a British crisped rice cereal called Coco Pops. He crossed the pond and graced Coco Pops cereal boxes in the U.S. from 1991 to 2001, when Kellogg’s decided to rebrand the product as Cocoa Krispies and put the elves Snap, Crackle, & Pop on the box. Although the monkey character was never pictured on a Cocoa Krispies box, 8.9% of study participants assumed that was his brand, more than the 5.9% who answered correctly.

Confusion over the dueling battery bunnies led to a settlement between Duracell and Energizer in 1992, after Duracell’s trademark expired. The companies finally agreed that Energizer would have exclusive rights to bunny-themed marketing in the U.S., and Duracell could use a rabbit mascot overseas.

Americans who work outside the entertainment industry might be forgiven for not paying too much attention to the opening credits before movies. Our focus is on the feature. Still, the Columbia Pictures’ “Lady with a Torch” has been gracing the silver screen since 1924, so it was somewhat surprising that 35.8% of study participants linked her with rival studios.

Sugar Bear from Golden Crisp was also linked with rival brands more often than his own, at a rate of 24.1% to 19.3%. Among insurance spokescharacters, “Mayhem” from Allstate was most likely to be confused for another company, with 10.9% of responses linking him with a rival brand.

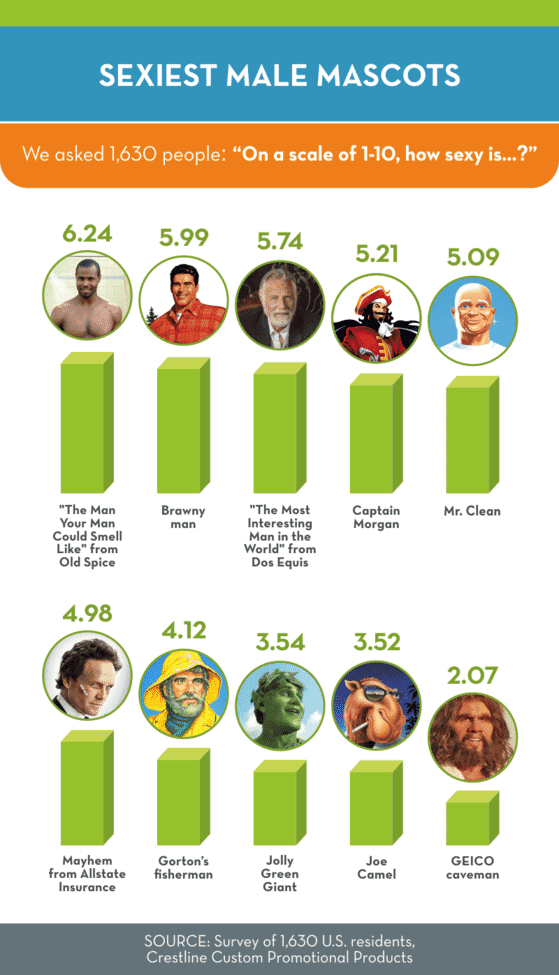

Fictional sex appeal

It seems Americans like their male mascots strong and clean-cut (or literally freshly showered). To find out whether consumers prefer Mr. Clean or the Brawny man, and what that might mean, our researchers put it to the test. Would Brawny’s wholesome, preppy good looks win, or would Mr. Clean’s bald head, earring, and twinkle of mischief prevail?

The results were pretty decisive. Mr. Clean and insurance bad boy Mayhem took a back seat to the Brawny man and Old Spice’s “Man Your Man Could Smell Like.” Among bearded characters, Dos Equis’ refined “Most Interesting Man in the World” beat out roguish Captain Morgan and the serious and moody Gorton’s fisherman. Although his clothing is always neatly pressed, GEICO’s disheveled caveman character came dead last in the rankings.

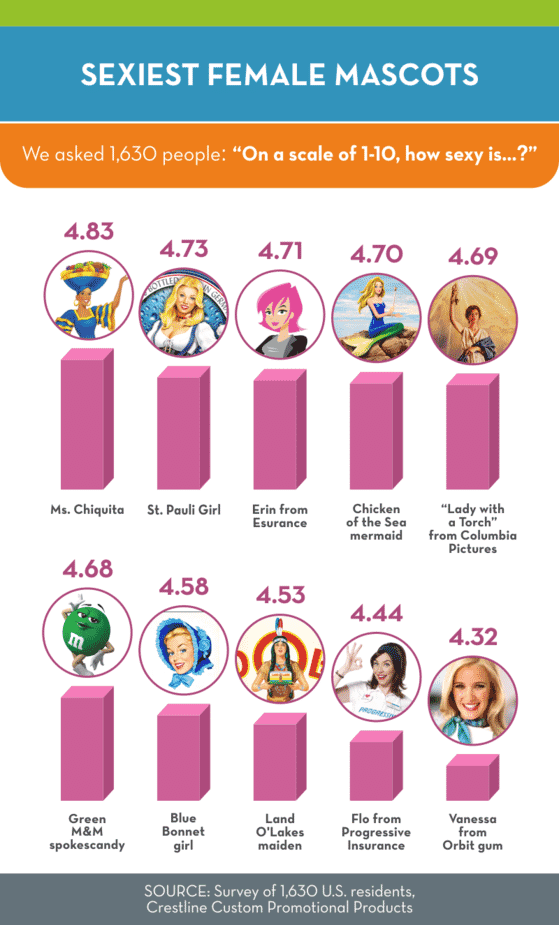

Interestingly, Americans seem to prefer their female mascots fictional. In terms of sex appeal, the eight imaginary women all outranked the two real women on the list. Ms. Chiquita, with her basket-of-fruit hat, was rated sexiest. Despite her bombshell good looks, Vanessa, the blonde spokeswoman for Orbit gum, scored lowest.

Esurance mascot Erin’s pink bob and leather catsuit ranked third among study participants, but was actually deemed too sexy during her brief stint as a brand mascot. The secret agent was introduced in 2004 but retired six years later because enthusiastic fans were drawing so much “adult art” featuring her character and posting it all over the internet. At the height of her popularity, 9 of the 10 top image results in an unfiltered Google search were lewd renditions of the Esurance icon.

Conclusion

Mascots are an integral part of marketing. While humans can and do portray brand characters, most companies still favor completely fictional ambassadors. Among the advantages: Illustrated mascots don’t age, so they can keep pitching the same product for a century or more. And cartoons, exercising no free will and living no personal lives, aren’t likely to get caught up in scandals that might tarnish a company’s image. (Remember Jared from Subway?) But whether a mascot is fictional or flesh and blood, making a lasting impression on the American public can still be a hit-or-miss proposition.

Many of today’s mascots have been around for a very long time. For instance, the Michelin man debuted in 1898, almost a decade before Henry Ford released the Model T and at a time when tires were white instead of black. Today, 123 years later, he’s still recognized by 80.5% of consumers. Like many vintage characters that are still successful generations after their introduction, the Michelin man has undergone several makeovers to keep up with the times. That was true for most of the enduring, iconic characters in this study. We also found that nearly all mascots that speak now have social media accounts.

Connecting with consumers in today’s hyper-saturated media landscape isn’t easy. When it comes to mascots, it’s important to create characters who are likeable, persuasive, and trustworthy — and are also unique or interesting enough to be remembered.

At Crestline, we’ve been leaders in the promotional products industry for over 50 years, providing world-class customer service and an exceptional line of products. We realize the value of investing in brand promotion, and we have access to over 100,000 different custom promotional items that can be personalized to help your brand imagery stand out as unique and memorable.

Methodology

The study was conducted online, with a total of 1,630 participants. Questions included a combination of open-ended responses and multiple-choice rating scales. For open-ended answers, researchers strove to determine the intent of each respondent. They ignored misspellings and gave credit if responses were phonetically close.

The study participants were 53% female, 47% male. They ranged in age from 18 to 77, with a median age of 30. The group included 108 members of Generation Z (ages 18-22), 943 millennials (ages 23-38), 406 members of Generation X (ages 39-54), and 170 Baby Boomers (ages 55-73).

The margin of error was ±2.43% with a confidence interval of 95% based on the population of all adults in the U.S.

Fair Use

If you’re a blogger or journalist interested in covering this project, feel free to share or reproduce any of the images above. All we ask is that you please credit Crestline Custom Promotional Products and link back to this page so your audience can find out more about the project.